30 August 2009

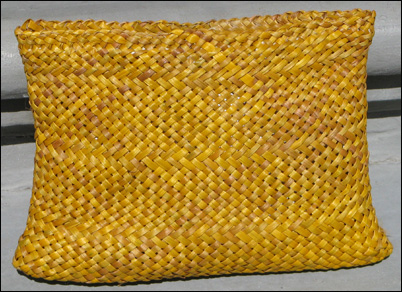

A plant with the common name cutty grass — with its reputation for cutting fingers if they’re run along it — is an unlikely plant to use for weaving, especially as its short, narrow blades limit its use. However cutty grass, or pīngao, a native coastal plant, has one quality that, for weavers, surpasses its apparent shortcomings and that’s the deep golden yellow colour that it changes to once it’s dried. The beautiful little kete pictured here, woven by Kohai Grace, shows the beauty of this rich colour. This natural colour has meant that pīngao remains a favourite weaving material, providing coloured patterning in tukutuku panels, ketes, mats and wall hangings.

A plant with the common name cutty grass — with its reputation for cutting fingers if they’re run along it — is an unlikely plant to use for weaving, especially as its short, narrow blades limit its use. However cutty grass, or pīngao, a native coastal plant, has one quality that, for weavers, surpasses its apparent shortcomings and that’s the deep golden yellow colour that it changes to once it’s dried. The beautiful little kete pictured here, woven by Kohai Grace, shows the beauty of this rich colour. This natural colour has meant that pīngao remains a favourite weaving material, providing coloured patterning in tukutuku panels, ketes, mats and wall hangings.

My interest in pīngao was sparked when one of the participants in a recent workshop brought some pīngao blades along to weave with. Karen, who bought the little Kohai Grace kete a couple of years ago, had been growing the pīngao for three or four years and it had reached the stage where the blades were long enough to use. The blades are mostly midrib with a small amount of soft leaf each side, and with one side narrower in width than the other. The blades are quite hard but soften very easily when a knife is run along them. Karen discovered very quickly that it was wise to have gloves on when softening the blades as it lived up to its name of cutty grass. She also found that she didn’t need to soften the pīngao as much as she normally would with flax and that the narrowest side of the blades tended to split off. She ended up removing this narrow side on all the blades although she may not have needed to if the softening hadn’t been quite as vigorous.

My interest in pīngao was sparked when one of the participants in a recent workshop brought some pīngao blades along to weave with. Karen, who bought the little Kohai Grace kete a couple of years ago, had been growing the pīngao for three or four years and it had reached the stage where the blades were long enough to use. The blades are mostly midrib with a small amount of soft leaf each side, and with one side narrower in width than the other. The blades are quite hard but soften very easily when a knife is run along them. Karen discovered very quickly that it was wise to have gloves on when softening the blades as it lived up to its name of cutty grass. She also found that she didn’t need to soften the pīngao as much as she normally would with flax and that the narrowest side of the blades tended to split off. She ended up removing this narrow side on all the blades although she may not have needed to if the softening hadn’t been quite as vigorous.

Karen wanted to use the whole length of her pīngao blades and so wove a kete that was joined at the bottom, ending up with a kete about twelve cm high. She plaited around the top, continuing the plait with the remaining lengths until they were used up and then wound this thick plait around the top of the kete. As Karen wasn’t happy with her first attempts, the pīngao strips were worked quite a lot as she undid and rewove her work and the stress on the blades, where they’ve split and shredded, can be seen in the photo here. However, the final kete has its own character and uniqueness and is attractive as a whole.

Karen wanted to use the whole length of her pīngao blades and so wove a kete that was joined at the bottom, ending up with a kete about twelve cm high. She plaited around the top, continuing the plait with the remaining lengths until they were used up and then wound this thick plait around the top of the kete. As Karen wasn’t happy with her first attempts, the pīngao strips were worked quite a lot as she undid and rewove her work and the stress on the blades, where they’ve split and shredded, can be seen in the photo here. However, the final kete has its own character and uniqueness and is attractive as a whole.

Although pīngao, a sand-binding plant, whose long trailing rhizomes help to stop erosion on sand dunes, once grew plentifully on coastal sand dunes throughout New Zealand, its growth declined rapidly as a consequence of burning and grazing by wild and domestic animals and overgrowth by marram grass. Harvesting methods have also contributed to this decline. Studies show that cutting a whole leaf cluster from the plant or wrenching the blades from the plant damages the growth. Clipping individual blades is now recommended as the most desirable harvesting method as it means only the useable blades are cut and that the plant is not damaged during the process.

Although pīngao, a sand-binding plant, whose long trailing rhizomes help to stop erosion on sand dunes, once grew plentifully on coastal sand dunes throughout New Zealand, its growth declined rapidly as a consequence of burning and grazing by wild and domestic animals and overgrowth by marram grass. Harvesting methods have also contributed to this decline. Studies show that cutting a whole leaf cluster from the plant or wrenching the blades from the plant damages the growth. Clipping individual blades is now recommended as the most desirable harvesting method as it means only the useable blades are cut and that the plant is not damaged during the process.

As I don’t have ready access to harvesting pīngao, and it seems to be relatively easy to grow, I decided to grow some pīngao plants in my garden. I bought six plants, grown from seed sourced from Kaitorete Spit, from the Department of Conservation nursery in Motukarara. George Santos, the manager of the nursery, advised that although pīngao’s natural habitat is sand, it can grow in ordinary soil, the vital component being a well-drained situation. I’ll plant mine in a well-drained spot in my garden but they can also be grown in pots in a mixture of sand and potting mix, as Karen grows hers. Landcare Research has information on their website about growing pīngao and there is good information in the book Pīngao: The Golden Sand Sedge mentioned on the Reviews page of my website. So there’s no need to have a sand dune in your back garden to grow this valuable weaving resource!

As I don’t have ready access to harvesting pīngao, and it seems to be relatively easy to grow, I decided to grow some pīngao plants in my garden. I bought six plants, grown from seed sourced from Kaitorete Spit, from the Department of Conservation nursery in Motukarara. George Santos, the manager of the nursery, advised that although pīngao’s natural habitat is sand, it can grow in ordinary soil, the vital component being a well-drained situation. I’ll plant mine in a well-drained spot in my garden but they can also be grown in pots in a mixture of sand and potting mix, as Karen grows hers. Landcare Research has information on their website about growing pīngao and there is good information in the book Pīngao: The Golden Sand Sedge mentioned on the Reviews page of my website. So there’s no need to have a sand dune in your back garden to grow this valuable weaving resource!

© Ali Brown 2009.

Scroll down to leave a new comment or view recent comments.

Also, check out earlier comments received on this blog post when it was hosted on my original website.